We are not alone!

My mother’s advice during my childhood is now coming to mind. She told me to avoid washing my face with soap because – she said – it would ruin my skin because it wiped away the “natural protective substances” our skin had. That really stuck with me, and, ever since, I have followed this rule almost to the letter. And who knows if, thanks to that, I have a few less wrinkles!

This position had its merit at a time when all germs were considered to be an enemy of the body and should be eliminated because they were potentially pathogenic. So, logically, they had to be wiped out, even using antibiotics, the discovery of which was one of humanity’s great milestones.

Today, things have changed, as was shown a few years ago with the techniques of massive microbial DNA sequencing (NGS techniques). We now know that no, we are not alone!

This is so because there are as many bacterial cells existing in our bodies as the number of cells we have. In other words, 50% of our body’s cells are microbes – one bacterium per cell, approximately – and this means that between one and three per cent of our weight is bacteria. In fact, we carry around a kilo or more of bacteria without even realising it.

We have known for many years that animals and humans are carriers of micro-organisms. Until very recently, these have been treated with great indifference. In fact, it was believed that it was important for health that they did not exist because they posed a threat of causing infections when our defences are low. Now, let’s not fall into the COVID trap and return to the old theory of exterminating all “living bugs” audacious enough to get near us.

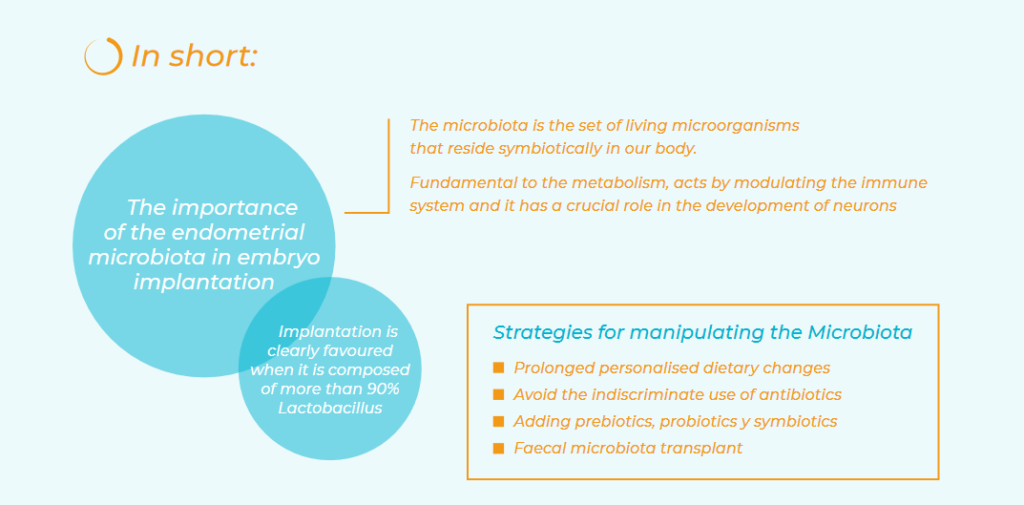

The microbiota is the set of living microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, fungi and others) that reside symbiotically in our body. These microbial ecosystems are found in the gastrointestinal, genitourinary and reproductive, and respiratory systems, the oral and nasopharyngeal cavity, and the skin.

Until the beginning of this century, we had accepted the dogma that babies were born sterile, and that some organs – such as the uterus – were also sterile. However, using molecular mass sequencing techniques, we now know that the foetus in the uterus already has microbes. Logically, they come from the mother.

The uterine cavity was classically considered a sterile place, but this dogma has also been disproven in recent years. Now, we are learning more and more about the importance of the endometrial microbiota in embryo implantation. The endometrial microbiota is, by the way, different to the vaginal microbiota, which has been studied the most widely due to its easy accessibility. Studies of endometrial microbiota show that uterine implantation is clearly favoured when it is composed of more than 90% Lactobacillus. This is why we advise a systematic study of it in patients with implantation failure. The trend is to expand the study to more cases and to create personalised treatments.

This means that the endometrial microbiopsy is done via a Pipelle in the office. It is easy to do and there is very little discomfort, and makes it possible to determine the intrauterine microbial DNA using modern NGS techniques.

How does the microbiota act in our bodies?

The most obvious way is the nutritional role of intestinal microbes that are fundamental to the metabolism of multiple substances. The defensive role of certain microorganisms, such as Lactobacillus, in colonising an organ and occupying the space to prevent the proliferation of pathogenic organisms is also becoming more widely known.

The microbiota also acts by modulating the immune system, which is specific to and different in each person. It also has a crucial role in the development of neurons and cognitive functions, through complex communication between the products of the intestinal microbiota and the central nervous system by means of what has been called the “gut-brain axis”. This means that neurotransmitters produced in the intestine by bacteria, such as GABA, noradrenaline, acetylcholine, etc. can travel through the vagus nerve.

It is becoming increasingly known that changes in the microbiota influence the emergence and development of diseases, such as diarrhoea due to Clostridium difficile, colon cancer, metabolic and neurological diseases, oral health and changes in the genitourinary and reproductive apparatus.

How can the microbiota be manipulated to improve health?

There are two types of strategies, with some modulating the existing microbiota and others aimed at adding new germs to colonise the organism.

1. Strategies that modulate the microbiota:

Dietary changes change the microbiota temporarily, but prolonged personalised dietary changes could be maintained to achieve permanent changes. Avoid the indiscriminate use of antibiotics: they alter the microbiota, so they should be used only in clearly necessary cases in order to prevent resistance. Lastly, prebiotics, which are nutrients not digestible by the human digestive system but rather stimulate and encourage the growth and activity of intestinal bacteria. Thus, they do not contain living microorganisms.

2. Strategies for adding new microorganisms:

Such as probiotics – food supplements that contain strains of bacteria and living yeasts aimed at colonising the affected organ – that leave no room for pathogens and even annihilate them by carrying bioactive molecules harmful to them. Others are symbiotics, which are food supplements that contain a combination of a microorganism (probiotic) along with a carbohydrate (prebiotic) that benefits microbiota growth.

Lastly, another, more novel, strategy is the faecal microbiota transplant. This attempts to replace a patient’s intestinal microbiota with that f rom healthy donors with healthy cultures, or even autotransplantation.

However, restoring the microbiota in the event of a disease is much more complicated than we could imagine. This is because millions of interactions between the organism’s bacteria and cells take place in the microbiota. At the moment, the only treatment that seems truly effective is faecal transplant for treating recurrent Clostridium difficile infections. Some newborns are benefitting from it when other, prior, treatments were ineffective.

The treatment of women with altered endometrial microbiota is also beginning to bear fruit in cases of implantation failure in which a uterine microbiota with a content of less than 90% lactobacillus has been detected. In these cases, the uterine flora must be replenished by the administration of Lactobacillus of various strains, both orally and vaginally, beginning one or two months before embryo transfer. By the way, we are already beginning to hear about the “endometrial virome” in these COVID times.